The LGBTQ+ community was instrumental in progressing cannabis legalization.

At a time when it is possible to drive down the road to your local dispensary and purchase safe, high-quality cannabis free from fear of persecution, it is easy to forget the long and arduous road taken by activists to get us where we are today. Even less acknowledged is the fact that such cannabis activism is deeply rooted in the LGBTQ+ community’s long struggle for equal rights.

For many years, LGBTQ+ individuals and cannabis users were (and continue to be) the subject of discrimination, criminalization, and even violence for matters pertaining to one’s personal lifestyle. In this sense, LGBTQ+ and cannabis advocates were perfectly suited for pairing up — and that is exactly what many of them did. Furthermore, were it not for the powerful voices of pro-pot LGBTQ+ activists, it is doubtful that we would have the freedom to consume in many places today.

Read on to learn more about the history of LGBTQ+ and cannabis activism, and how it has paved the way towards legalization.

Seeds of Change

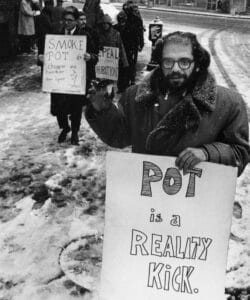

Allen Ginsberg at a LEMAR rally outside of the Women’s House of Detention in New York City, 1965.

As a pioneer of the countercultural movement of the Cold War Era, it makes sense that Allen Ginsberg — a gay, Jewish poet of the Beat Generation — would be a force of change for traditional ways of thinking about sex and drugs. He is largely credited with being the first mainstream figure to publicly challenge notions about cannabis use, thus causing many to question the legitimacy of its illegality.

Ginsberg changed the narrative when he argued that cannabis had medical and spiritual value; that people consumed it to open their minds to new ways of thinking and escape the stresses of everyday life. For homosexuals in particular, who faced the brunt of the police’s reactionary efforts to clamp down on the use of illicit drugs, cannabis was a crucial part of dealing with the trauma that comes with existing as a stigmatized group of individuals.

As a grassroots activist in the truest sense, Ginsburg traveled to every state and numerous countries, preaching about everything from pot to LGBTQ+ rights, free speech, pacifism, and the environment. He was an expert in guerilla activism, staging “smoke-ins” and marches, publishing educational magazines, leaflets, and newsletters, hosting readings to raise funds for imprisoned activists, appearing on national television, and helping establish local pro-legalization groups such as New York City’s LEMAR (Legalize Marijuana) Chapter. He was expelled from several countries and served time on multiple occasions. But despite these setbacks, Ginsberg became even more dedicated to enacting his mission of promoting peace, equality, and drug reform.

Roots Take Hold

While Ginsberg’s activism set the stage for a cultural revolution, perhaps his most important legacy was the sway he held over future activists.

Dennis Peron was one such protégé. A gay Vietnam War veteran, Peron moved to San Francisco’s Castro District following his time in combat. As a lifelong cannabis lover, Peron took refuge in the countercultural mecca Allen Ginsburg helped to create, where he established the first undercover pot shop under the guise of a health foods store. The Island, as it was called, became a hotspot for Yippies — it was an oasis for homosexuals, stoners, environmentalists, and the likes to come together to plan and discuss political change.

In remarkably similar fashion to Ginsberg, Peron was a natural-born grassroots activist and an expert in civil disobedience. He despised having his personal affairs monitored and policed. He regularly preached the benefits of the herb on Hemp Tours, was busted on multiple occasions, and of course, held daily smoke-ins right in his restaurant.

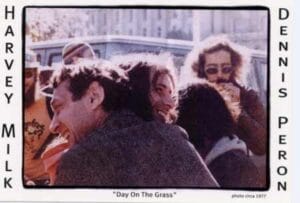

Harvey Milk (front) & Dennis Peron (back)

Meanwhile, as San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ community grew, so too did their political power. In 1977 — with tremendous support from Peron — Harvey Milk became the first openly gay man to be elected to public office. As City Supervisor, Milk enacted protections for the gay and lesbian community, advocated for civil rights, worked with local labor rights advocates, and even defended Peron in court after The Island was raided (the shop even served as Milk’s campaign headquarters for a period of time).

Milk and Peron worked together to pass Proposition W, which would have decriminalized the manufacture, sale, and possession of cannabis in San Francisco. Unfortunately, implementation of this non-binding referendum — which passed with overwhelming support — was derailed, as Harvey Milk was assassinated in 1978 by a disgruntled, homophobic ex-cop named Dan White.

From Flame to Fire

While Peron was always an ardent medical cannabis advocate, his activism intensified after his lover, Jonathan West, died of AIDS in 1990. Cannabis helped West tremendously with symptoms such as nausea, loss of appetite, and neuropathic pain, but when Peron was again arrested, the sick man was unable to secure a reliable source of cannabis to help manage his symptoms. West lived long enough to testify on behalf of Peron and passed away several weeks later.

As the HIV/AIDS epidemic ravaged the gay community with little support from the federal government, Peron made it his mission to supply the sick and suffering with free cannabis. The Island had been shut down during the raid, but Peron nevertheless persisted and set up The San Francisco Buyer’s Club just down the street — the first medical marijuana dispensary in the United States. The Club was able to operate openly because of the passage of a referendum he helped craft, Proposition P, urging the City of San Francisco to legalize cannabis products for medicinal use. Peron was not safe from persecution under the referendum (and indeed, the shop was raided in 1996), but he knew that voters’ overwhelming support of the measure afforded him some level of protection, and it was worth it in his mind to continue helping the sick — even if it meant risking his own livelihood.

San Francisco Cannabis Buyer’s Club EdRosenthal.com.

Using the Club as headquarters, Peron eventually went on to co-create Proposition 215. Also known as the Compassionate Use Act, the referendum passed in 1996, effectively legalizing marijuana for qualifying medical conditions in California.

While opposing political forces in the federal government delayed implementation of the voter-approved law, the Compassionate Use Act nevertheless ushered in a new moment in the War on Drugs. It is no wonder that Peron is commonly called the Father of the Medical Cannabis; as of today, 37 states and the District of Columbia have medical marijuana laws, and 17 states (and counting) allow recreational cannabis sales to anyone over the age of 21.

The Fight Isn’t Over

To this day, neither LGBTQ+-identifying individuals nor cannabis users are entirely free from stigmatization. Whether a person comes out of the closet in terms of their sexuality or their cannabis use, there still exists the potential to be discriminated against. Indeed, there will always be more work to do when members of marginalized groups such as the LGBTQ+ community and people of color face violence simply because of who they are and what they do in their personal lives.

That being said, today we celebrate the contributions made by LGBTQ+ activists in advancing cannabis policy reform. So, the next time you light up, take a moment to appreciate how far we have come and the sacrifices made by so many brave people working to get us where we are today. In addition, learn more about how you can show your support for the LGBTQ+ community by visiting Torrey Holistics’ Pride Guide.

These statements have not been evaluated by the FDA. Nothing said, done, typed, printed or reproduced by Torrey Holistics is intended to diagnose, prescribe, treat or take the place of a licensed physician.

About the Author

References

“Allen Ginsberg: Biography.” The Allen Ginsberg Project, 30 Apr. 2018, allenginsberg.org/biography.

Lee, Martin A. Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana — Medical, Recreational, and Scientific. New York City, SCRIBNER, 2012.